Pacing…oh where to start?

Pacing is one of those phrases that’s impossible to ignore if you’re any way involved in the chronic illness sphere. Scratch that, if you’ve seen any kind of medical professional about a chronic illness full stop.

It’s touted as one of the most important tools when it comes to helping us manage our long-term health conditions – but I’ve yet to find a way to make it truly work for me, or even had it explained in a way that makes sense for my life. And I received my first diagnosis nearly a decade ago.

That’s a long time to know about pacing, but not really know about pacing.

I suppose my earliest memories of being told to pace was to just “do less” and “expect less” of myself. There was an expectation that there were some things I should just do (or, I suppose, not do) without really addressing the grief and the frustration that would come from it.

I was definitely given the contradictory commands of keep as mobile as possible but also rest more (aka do less). And whole that ‘do less’/’expect less of yourself’ thing is pretty much the extent of the pacing advice I can remember.

Being told these things at 21 in a way I couldn’t connect with, or given any actual helpful, tangible information or skills for how to do it, only made me more entrenched in my boom/bust cycle of only stopping when I pushed myself too hard.

Now, as a <jennamarbles>31 year old lady</jennamarbles>, I have the benefit of both hindsight, and a whole lot of experience of living with chronic illness, and I fundamentally believe that one of the biggest barriers when it comes to medical professionals talking about lifestyle management and the psychological elements of living with a long-term condition is the way in which it is presented.

Realistically, I have conditions that are under-researched, under-funded, and under-supported. Which means that right now, lifestyle management is pretty much the best bet I have to function as well as I can.

But I’ve often found that the impact of this on a patient, and the way in which some of these things are even talked about and explained can be counter-productive, making people feel angry, upset, and defensive. It’s more a command of ‘do this’ without a kind and empathetic explanation of what to do, how to do it, and why this could be of benefit.

Instead, they’re often presented in a way that puts a huge burden on patients to manage their conditions – without actually being given tangible, helpful tools to be able to achieve this.

Disclaimer Alert: Before we get into anything, I want to make it very clear that this workshop was tailored to me and my body needs right now. Anything I talk about may be too much or too little for you – and that can change on any given day. Remember to never base your health outcomes on what you see others doing online, and make sure to do what is safe for you.

Why am I doing a pacing workshop?

If you follow me on Instagram, you may have seen that I’ve been experiencing a bit of burn-out and frustration as I’ve tried to increase my activity levels and expectations of myself, only to push way too far and crash physically and mentally.

I will say, over the years, I’ve done a lot of work on figuring out my priorities, and made a lot of compromises that have enabled me to have a life now that I could only have imagined a few years ago. And part of that is implementing elements of pacing that are now second nature.

But a lot of what I do is more physical pacing, as opposed to everything-else-pacing, and I know this has a substantial impact on my functioning day-to-day. But I just…can’t….seem to bring myself to do it all. The idea of what I’d been presented as pacing ‘activity and then full cognitive rest’ often felt impossible.

I also find that I experience what I call ‘responsibility fatigue’ – where I know there are a bunch of things I need to do every day for my mental and physical health, but on top of my real job, trying to maintain a social life, and running my blog/social media – when I stop I just want to half stare at YouTube until I fall into a restless slumber – and it’s a constant balancing act between all those health things and other life things, and I find one always seems to win out one way or another.

When I have an energy uptick, I tend to spend it on doing all the things I had to stop for so long – only to then have used everything I’ve got on that and something like my exercises or trying to learn to relax goes out of the window. And I beat myself up for that a lot.

So, because I’ve never done a proper deep-dive into pacing beyond being told to take more cognitive rest (helpful, ta) and finding the pacing worksheets incredibly counter-intuitive and unhelpful, I thought that reaching out to an expert for help (and documenting the process because a lot of people have said on Instagram they also struggle with this) could be a great place to start.

Ok, so what’s the deal?

In September, I was lucky enough to interview the lovely Maike all about Occupational Therapy and how it can help people living with long-term health conditions.

As I was putting the post together, I realised that this was something that could potentially make a substantial difference to my quality of life, and added it to my list of things to look into in the future.

Out of curiosity, I asked my GP about OT, and he told me that it was something that I could be referred to on the NHS, and so wanted to just share that here. Obviously, I don’t know if this is available in all areas, but it’s absolutely worth asking if it’s something you’d be interested in.

But because I have some specific #content ideas around OT, I wanted to wait on being referred, and I’m glad I did.

I recently came across Jo Southall, a licensed Occupational Therapist who has EDS and regularly works with the Hypermobility Syndromes Association, and learned that she offered many different kinds of OT services online. So I thought she’d be a great person to reach out to in my new-found quest to learn about pacing.

Jo very kindly agreed to be interviewed as part of this little experience, and after exchanging some emails and explaining how she works, we decided that it made the most sense for me to start off with her Pacing Masterclass.

The Pacing Masterclass

The Pacing Masterclass is a 30 minute video session (with the option of extending) which costs £20, although there are payment plans available.

You can get in touch with Jo via the form on her website, and she will then email you. Once we decided this was the initial route we wanted to go down, she sent me an interview form.

This covered basic data protection, cancellation policy, video chatting information, and my general rights. I was asked to sign and date, which I did digitally. It then asked for my contact information and preferred methods of how we’d video chat, as well as my preferred contact methods. So far, so standard.

The form then went on to ask about my diagnoses, symptoms, mobility, self-care, productivity, leisure, and anything else about my conditions I may want her to know about. I tried to go into some detail here, but because we knew very specifically what we wanted to cover, I didn’t word-vomit everything (which is good for me cos I bloody love words).

The final sections were about what kind of appointment I’d like, what my goals would be, when I would be available, and a consent for her to contact my healthcare provider/share reports with them (but only if I wanted to).

I then emailed this back to her, and we agreed a time and a video software to use to chat (we decided on Zoom).

Jo then sent me an invoice via PayPal – she requires a £5 deposit up-front to reserve the booking – but you can also pay the full £20 in one go if you prefer – which I did.

Once I had paid, Jo sent me the Pacing Masterclass Handout, and we said goodbye until our session.

The Handout

I was told that I didn’t have to read the handout before our session, as Jo would be going over everything in detail when we chatted. But I was too curious not to! I decided to print mine off. I like having important things in hard-copy because I retain the information better than if I scan it on a screen.

The handout itself if an 11 page word document which covers the basic elements of pacing (aka wtf is pacing, actually, and why is it important?), and a series of tools that can help with understanding it.

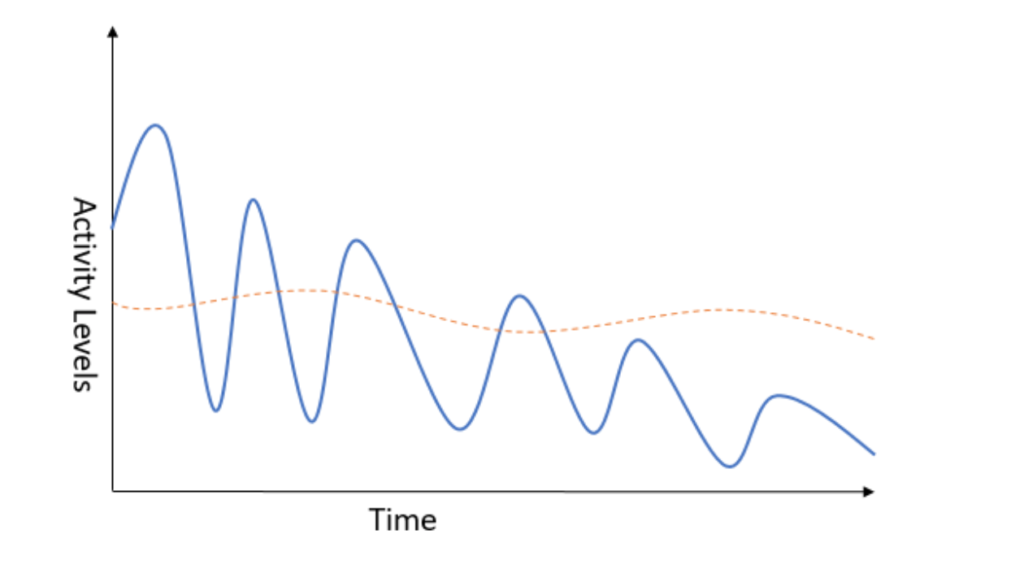

I have to say, this was probably one of the first things I’ve ever read that clearly and concisely explained what pacing was. Especially her example of the boom-bust cycle which pretty much could be tattooed on my body as to how ‘me’ it is.

It turns out that boom and bust can be so much more than just a ‘bad day and then a good day’ – those patterns can be over hours, days, weeks or months.

The ultimate aim with pacing, and my goal with this little series, is to learn how to keep things more stable over time (as represented by the orange line in the image below) instead of those peaks and troughs.

Our video session

We started off with Jo asking me what my current knowledge of pacing was, and how I utilised it in my day-to-day life. This was to make sure she wasn’t spending a whole lot of time going over stuff I already knew – which I very much appreciated!

I told her how I think I’ve kinda got the ‘big’ pacing stuff down – things like figuring out how to work sustainably from home, resting before and after going out, saying ‘no’ to things, etc.

It’s more the day-to-day pacing stuff that I struggle with the most. And more than anything, I struggle with the concept of ‘proper rest’ and how to implement that throughout my day. I’m very good at pushing through, but this is often to my detriment.

I’m not going to go into all of the specific details here, but I thought I’d share a bunch of my biggest takeaways from the session, the major lessons I learned, and what I’m hoping to work on implementing over the next few months.

Because this posted ended up being quite long, I’m also writing a follow-up post, where I put a bunch of more specific pacing questions that I had, and fantastic ones that other people shared with me on IG Stories, to Jo. So keep your eyes peeled for that and subscribe to my mailing list!

The first thing I have to say is that I was thoroughly impressed. Jo is clearly very knowledgeable, but she also has first hand experience as a patient, so there was an instant level of understanding there.

I genuinely felt like she explained concepts to me in a way they had never been presented before, and I left our call feeling like I had an entirely different perspective on what pacing was.

Jo describes pacing as: “the art of breaking your life into small, manageable micro-tasks. When pacing a person takes regular short breaks to avoid symptoms as opposed to one very long break to recover from them.”

It’s funny, really, because so much of it is just so simple – really basic techniques, but sadly these often are so badly communicated (or in my case not really communicated at all), so people are just left to muddle through and try the best that they can.

I left the session feeling as though it was the type of thing anyone newly diagnosed with an energy/pain limiting chronic condition could benefit from, and made me wonder about what difference it would have made to my overall quality of life if someone had bothered telling me this stuff a decade ago.

The four biggest takeaways for me were that:

- Pacing doesn’t have to be blocks of activity followed by blocks of full cognitive rest. This is something that I always struggled to do – and was pretty much the extent to which pacing had been explained to me in the past. So when she said this it was like I just sighed an existential sigh of relief.

- Pacing shouldn’t be a thing that makes us feel as though we’re able to do less and having to restrict. Of course it can be a real challenge, but the aim of it is to enable us to do more things in a more sustainable way over time.

- Pacing needs to be proactive not reactive. That it’s better to take a short break before you need to not after you already start to feel like utter shite and need to take a substantially longer break to recover.

-

The concept of a ‘baseline’ isn’t necessarily helpful for people with varying health. It can cause confusion, and we can spend a lot of time trying to work out what we can and should be doing, instead of living our lives.

Changing Activities

This was absolutely the biggest takeaway for me.

As it turns out, unless it’s one of those times when my body literally just needs silence in a dark room, feeling pressured into multiple chunks of full cognitive rest every day is not necessarily the most helpful, necessary, or important thing for me in terms of pacing.

There are two techniques that I can use to help make the most of the energy I have, whilst conserving and protecting what I need in the long-run.

The first one, which is probably the main thing I’m going to try to implement, is the idea of pacing between different types of activity: a physical task, a mental task, and a recovery task.

So, for example, a physical task could be preparing food or washing my hair, a mental task could be writing this blog post, and a recovery task could be something that I know makes me feel better health wise (lying down with a heating pad) or something that I find relaxing, like watching Bon Appetit on YouTube.

I love Claire.

So, instead of sitting and writing until my brain is screaming and then lying in bed feeling terrible until I can move again, I would switch between these three different types of tasks because they all use a different type of energy.

Overall, it will take me the same amount of time to actually do what I need to do, but I would be more protective of my energy, and use it in different places. The aim of this is to (hopefully) prevent me burning out on one activity and needing longer to recover.

One way I’m trying to implement this is by using the Pomodoro Technique when I’m working. It’s something I had been looking into a few days before we had the session – but I used it while writing this post, and I was actually surprised at how much I liked it.

Essentially, I set a timer (I use Toggl which has a Pomodoro option), and I will get a reminder when I have worked for the amount of time I’ve specified. This way I’m working in a short burst of concentrated time (instead of the way I grew up managing my health which was literally working in bursts but really unconcentrated and very reliant on my energy), getting a tangible and visible piece of feedback that it’s time to take a break, and then I can move on to either a restful activity or getting up to get something some food.

This also applies to something as simple as making something to eat. Instead of doing all of that in one go – how can I break that down into smaller chunks, and then sprinkle that out over a longer period of time: so like, go and chop something, and then do some writing, and then make a dressing, and then go and rest in bed, etc etc. By the time it comes to ‘cook’, it’s more throwing things together, instead of standing up for ages, lifting things, and getting so exhausted that I can’t eat.

A major thing that I’ve been struggling with is finding time to do all my ‘health stuff’ when I’ve upped my ‘work stuff’, and Jo made a fantastic point that I don’t need to do all my PT exercises (for example), in one go.

I can spread them out throughout the day, if that’s what my energy requires, and that it’s better to do one exercise perfectly, than 50 reps badly that then knock me out. Or no reps at all.

The Micro Break

The other type of break Jo mentioned was the Micro Break. This is a way of taking a tiny breaks without disrupting the flow of what we’re doing (which can be especially helpful when I’m doing something like writing, for example).

This can be done by finding ways to integrate good habits like sipping water, fidgeting, or relaxing for 10-20 seconds when we’re doing specific tasks. Like, when pressing send on an email, take 20 seconds to look away from the screen and fidget and get some water.

When you live with a chronic illness, it’s very common to be able to push through the small things that can very easily turn into a big thing – like those small aches or injuries or headaches that could be dealt with but may not be in time. These micro breaks are a way to check in with ourselves and solve the little things before they become more of an issue.

Breaking Bad (Habits)

One of the things I appreciated the most about Jo was that she understands where many of my bad (or less than ideal) pacing habits came from – they were me doing my best to learn how to cope as well as I could when I wasn’t receiving the support that I needed.

Sadly, this is the case for many people with chronic illness, and it means that there can be decades of habits to unpack and figure out – which can be a particular challenge when many of these things were implemented to try and help you in the first place.

But one thing I learned in 2019 was that many of these habits that may have helped me when I was younger, no longer do, and slowly working on changing them has been vitally important for me.

Jo told me that a therapist once told her that changing a habit can take two years – and that’s a really daunting thing.

Pacing definitely requires definitely more thinking to start with – I’m basically asking myself to make a big lifestyle change. But over time, that will become a part of my new ‘normal’

So What Now?

Well, I guess I have to start learning to pace!

As I mentioned, I’m not sharing everything that we talked about in this post because that would be totally unfair to Jo! I just shared the biggest things that I learned – there was also a lot of information about things that I’ve kinda learned over the years that I think would be really helpful for more newbie pacers.

Jo also points out that pacing is part of an overall management plan – that can include things like physiotherapy and medication for pain management (this is, of course, different for everyone). She told me that she would never say that she can make someone ‘better’ – but the aim with pacing is to teach coping strategies and skills that improve quality of life and can help people to manage the ups and downs of chronic illness more successfully.

The first, and most important, thing I need to remember is not to try and just implement everything at once and expect that I can really easily make changes – it’s decades of habits that I’m going to have to undo here.

The phrase ‘be kind to yourself’ is something that I’ve always hated – but I guess it’s true here. Blah.

I think it can be quite easy to fall into ‘pacing perfectionism’, where we feel as though we need to get it all right – but that is, in my experience, impossible. We live in the real world, after all.

So, trying to implement these things in a way that becomes more a natural part of my life (just like resting before and after an activity is) and it becomes second nature is ultimately the aim – and to take things one step at a time and know that it’s ok if certain techniques don’t work for me, my lifestyle, my personality, and my health.

I know that, for example, making really solid plans, and tracking absolutely everything to time is not helpful. So, what I’m going to do is take a bunch of the tips Jo shared with me and use them in a way that makes sense for what I like to do. But hopefully by ‘automating’ more of my ability to pace, I’ll be making more conscious decisions about my energy spend, instead of living in a perpetual boom-bust cycle.

I’m starting with the shifting blocks of energy thing and especially using this more concentrated form of working when it comes to my writing. I’m also attempting to get a little set-up so the first time in years, I can work out of my bed even for a small amount of time, because instead of just jumping in and out, I can dedicate small bursts of time, and know that I can move again soon.

I also spent the week and a half before 2020 trying to get my blog/Instagram life more organised and completely shifting how I manage this – and it has already been a huge relief. I’ll be sharing some of the organisational stuff in more detail on my Instagram Stories over the next few weeks.

Overall, I’m feeling really optimistic about this. It does feel a bit daunting, because it’s yet another thing that requires more conscious effort – but I’m hoping that it’s an effort that will pay off. The small things I have already done in the last week and a half, have already been things I have liked and want to continue. I tend to find I can do it for a few hours after I’m able to get out of bed and then am wiped out – but Jo reminded me to celebrate any wins.

One thing I really appreciated about Jo is that she also was incredibly realistic. She understands that there are always going to be times or reasons why we are not able to (or even choose not to) pace something: for example, there are times when I have no way to pace work and I know I need to recover after that. Or I may want to go to an event even when I don’t necessarily feel up to it.

What is important, however, is making it a conscious choice as much as possible, rather than floundering and throwing myself from one activity to the next. And that, I think, would be a nice place to be.

I really hope that this gives you an insight into pacing and was helpful for you! A huge thanks to Jo for giving me so much to think about! You can find her website at jboccupationaltherapy.co.uk, to learn more about her Pacing Masterclass and other services. You can also find her on Twitter and Instagram.

Because this ended up being way longer than I expected, I’ll be sharing another post in the next few weeks, where I put a bunch of specific pacing questions that I have, and other people shared with me on Instagram Stories to Jo. If you didn’t send me a question, please pop it in the comments below, and I’ll see what I can do!

If you enjoy my content, the biggest way you can support me is by subscribing to my newsletter .

8 thoughts on “I Did A Pacing Masterclass”

Oh this is amazing thank you so much. I find pacing so so hard, as i get somewhat overexcited about an activity and then end up crashing but I like Jo’s idea of breaking things into little chunks and your idea of using a timer too. Thank you!

You’re welcome! I’m glad it could help. I definitely can relate to the getting overexcited by an activity thing!

Great post! I have always pushed back when pacing is mentioned, but framed like this it does make sense. I think a difficulty for me will be to radically change my mindfulness of what my body is feeling. I have lived life constantly trying to ignore the pain until it’s unbearable, then take the meds and rest! This way I’ll need to get comfortable with being more constantly aware of pain/fatigue levels. Interesting!

Thank you ☺️ Yeah I definitely understand that! I went through that process a while back – it’s definitely a shift.

I think that Jo is great in giving you advice about pacing and how to break it into sections even if pacing can be difficult for most people.

Thanks Silvia!

Fantastic post. Really excited to try and implement these tips.

I’m so glad – thank you!