After the wonderful response to my last post all about what I learned at a Pacing Masterclass with Occupational Therapist, Jo Southall, I’m delighted to be able to share more information that I hope will help other people who haven’t had access to appropriate care and support when it comes to learning to pace, rest, and manage things like pain and fatigue.

I had a bunch of questions that I wanted to ask Jo, and I also asked my followers on Instagram to share what they wanted to know about pacing. I collated the most popular ones and you can read her responses below.

We cover the main misconceptions around pacing and resting, how to (hopefully) hate it less(!), tangible ways to start incorporating pacing into your day-to-day life, tools to help you manage big events, and more!

I hope you find this helpful!

So, let’s start off simply! How would you explain pacing to someone who was entirely new to it?

Pacing is the art of breaking challenging things down into easy to manage chunks. Doing the *thing* might be exhausting but doing little bits of *the thing* until it’s finished is much easier.

What would you say are the biggest misconceptions that medical professionals and patients have about pacing?

Probably that pacing means doing less. It’s actually doing less, having a break, then doing some more. Pacing is all about efficiency.

The better you pace the more you get done because you’re not spending so much time in ‘zombie recovery mode’.

I think OT’s and a lot of physiotherapists get it, but a lot of more ‘medical’ healthcare folks think it’s about avoiding hard things and laying down more, when it isn’t.

Why do you think so many chronic illness patients hate/struggle with the concept of pacing?

Honestly? Because it’s taught so badly! Or in a lot of cases not taught at all.

I’ve lost count of the people I’ve worked with who have been told ‘to pace themselves’ but not been told HOW to do that.

Bad pacing feels restrictive, so it’s easy to push back against because most of us are already fed up of how limited our bodies are.

Good pacing is freeing. It allows you to tackle things you though were impossible because as a whole activity they are! Little bits of the whole are much easier.

Can I knit a whole blanket in one go? Nope I’ll get tendonitis, carpel tunnel and finger blisters. Can I knit one blanket square a week? Absolutely. The result is a blanket but without the tendonitis.

What would you say would be the very first step for someone who is looking to incorporate pacing into their lives?

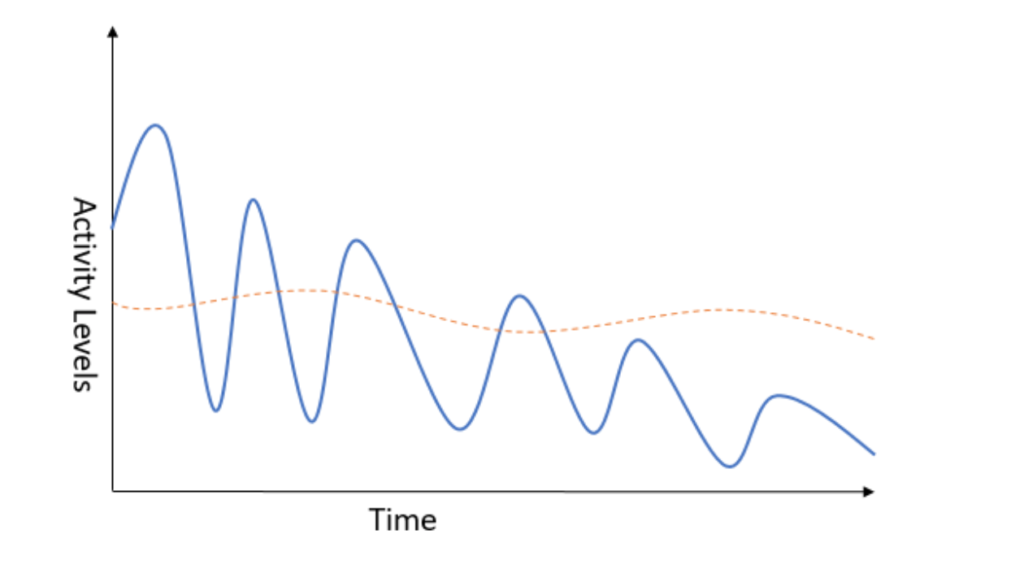

Start by recognizing which bits of your life need pacing. Are you stuck in the boom and bust cycle where you thrive for a little bit then crash spectacularly? If so, which bits of your life are causing that? Once you know what the ‘problem’ is you can work on fixing it.

Next time you come to tackle the problem activity, add in a few coffee breaks and try fidgeting more often. You might just find you’re less broken at the end of it.

How can someone make pacing fit into their life, rather than their life fitting into pacing?

This is a tough question! I think I pace my life but it doesn’t feel like a chore. It’s just my version of normal.

Changing your life to better manage your health isn’t a bad thing. Especially if it’s successful! That said, things like taking teensy little micro breaks to stretch while typing for long periods or changing how your sitting if you’ve been still for a while fit in perfectly with regular life, it isn’t an obvious coping strategy, it’s just normal human fidgeting.

Energy and pain levels can often be so variable – which can make it really challenging to plan pacing. What are some of your top tips for helping people with such fluctuating symptoms pace?

Get into the habit of breaking things into really small chunks, that way on bad days you’re still not pushing yourself too hard, on good days you can just do a LOT of small chunks.

Nobody ever had a flare-up from taking too many rest breaks.. taking too few on the other hand, can cause problems.

“Plan for the worse, hope for the best, unsurprised by anything in between” – Maya Angelou.

How do you decide what activities to prioritise?

There are two ways I generally recommend with this. Either pick the activities that have the biggest impact.

This can be things you have to do frequently or things that are *BIG*. Or, pick the activities that mean the most to you.

A lot of people mentioned that they find it hard to pace without feeling incredibly restricted – is there anything that can help with that?

I think, realizing that pacing doesn’t have to be alternating blocks of activity and rest, it can be alternating blocks of very different activities.

Knitting 10 rows then having to stop and rest feels restrictive. Knitting 10 rows then going for a walk round the garden feels good. The end result is the same, I’ve given my hands a rest.

And one of the main things that came up time and time again was about ‘resting’. What, in a pacing context is rest, and what are some ways for people to incorporate rest, consistently, realistically, and in a way that doesn’t feel demoralising, into their pacing plans?

A rest in the most simple sense is when you stop doing the thing you need a break from. It’s not actually all that often that ‘rest’ has to mean silence, stillness and a darkened room.

Rest from physiotherapy can be a chapter of a book, rest from answering emails can be a set of calf raises while looking out the window. Rest from ironing can be watching Netflix.

Often it’s about listening to your body, do you need to rest a bit of you? If so, can you do that while still using the rest of you. That said there will be times where you do need to just switch your body off with your eyes closed for a while…but maybe you can still listen to music.

I know from personal experience that on a ‘good day’ or during a bit of an upswing, it’s very easy to overdo it and push myself too far and then crash as a result. What are some ways to mitigate this, even when you want to do as much as you can!

This sort-of mitigates itself when you get good at pacing, if the pacing strategies are ingrained in your normal behaviors it becomes normal to pace everything. Likewise, if micro breaks are normal and easy, you do them naturally.

To start with I think it helps to be aware of the consequences of not-pacing. Once you’re stuck in with it the benefits start to show and it’s easier to sell it to yourself as a good idea!

What advice would you have for someone who experienced delayed crashes, and therefore finds it challenging to discover the cause?

This is REALLY common with a lot of my clients and is something I’ve struggled with myself. Often it takes a lot of practice at pacing everything to start seeing benefits. If you’re pacing everything then identifying the cause is less important.

Symptom diaries can be really good for this. If you start logging what you’re doing and how you’re feeling every day, you can begin to spot patterns like ‘two days after a food-shop I’m always half-dead’.

At that point you might consider using a mobility scooter in store, having a friend help, shopping more frequently but for fewer items or shopping online for most of the heavy stuff and just popping out to pick the best fruit and veg yourself.

There were a lot of questions about baselines – how do figure out where they’re at and how to (hopefully) increase it. I know you have some thoughts on baselines – can you share them? And how can someone know the difference between ‘overdoing it’ to try and increase their baseline and actually doing something that can help?

I really don’t like baselines…I realise this is a strange perspective for a healthcare professional but first and foremost I’m a person with seriously variable health and mobility. That person, hates baselines.

I generally take a ‘prepare for the worst’ approach here. Take breaks as often as you would need them on a bad day.

If you’re having a bad day do two sets of (insert activity here) with breaks between. If you’re having a good day you can do four sets of (insert activity here) with the same breaks.

This way it’s not the intensity or length of activity you change but how many repetitions of it you manage. Once you’re up to being pretty active without crashes, you can start fiddling around with intensity and longer periods of activity before breaks.

With a lot of health conditions, it’s much easier to maintain stability than it is to build back up after a big crash, so your best is building really slowly, rather than doing too much and spending a month in ‘recovery’ mode afterwards. Slow and steady always wins the race.

How can someone know if they actually need to rest or they need to keep moving to help with their pain?

Moving isn’t the opposite of pacing. You can move more while resting. I have a whole lot of pilates and yoga skills that work well laying down. A lot of them can be done in bed.

Gentle stretching can still be restful. I think the longer you live with a condition the better you get at listening to your body. Pay attention, and keep symptom diaries if you need to. Work out the correlations between every-day activities and symptoms. If in doubt, try a little of something and see how you feel.

What recommendations do you have for people trying to balance work and deadlines with their pacing? Is it ok if there are things that just can’t easily be paced?

Of course! You may be shocked to hear I still over-do-it at times.

Pacing 1 thing out of 100 is still pacing, it’s progress if you were previously not pacing anything!

Celebrate the little victories. If you manage to pace most things then you’re likely to manage the un-paced things a little better since your starting point is healthier and less burnt-out.

What are your top tips for pacing at an all-day event, like a wedding?

Events like these can be really hard. Pacing alone won’t solve this ‘challenge’. Pacing is part of a series of skills and equipment you need to self-manage like a pro.

Planning and prioritization come first –

For a wedding, I’d probably start my ‘prep’ a week in advance, plan an outfit, plan my hair, plan my travel.

Three days before a big event I start winding down work, two days before I make sure I do *all* the self care stuff, I can do in advance. The day before I rest. I prioritize my health over everything else. This planned rest day allows me to save as much energy as I can to carry over for the wedding.

The day of the wedding I’ll use mobility aids, I’ll have people help me with things I can ‘sort of’ manage rather than struggling. I’ll be sensible with my food and drink choices. I will pace and I’ll sometimes find somewhere quiet to crash out for a bit between big events.

For big events I always plan the following day as a rest day. If I’ve chosen to spend all day on the sofa watching Netflix then I have control over the situation. If I had planned to go out and my body decides it’s a Netflix day then I don’t have control over that and it feels like I’ve ‘failed’.

Pacing is one strategy of many, for big events you might well need a wheelchair or better pain killers, or a helper, TENS machine, compression tights, or some caffeine to get through. That’s ok. It’s not because you’re failing at pacing, you’re just using all the tools available to you.

What can people do when unexpected things pop up and their pacing plans get interrupted?

This is often one of the more challenging aspects at the beginning of a pacing journey. Often when I first start working with people they’re in ‘survival mode’. They have just enough energy to get the basics done, they are sort of keeping on top of everything but aren’t thriving.

In this situation when a disaster happens there’s no spare energy to deal with it. This causes all kinds of chaos and a post-chaos flare-up. If you’re not in survival mode and you do have a little spare energy, disasters are much easier to cope with. The better you pace, the more able to cope with disasters you are because you’re further away from survival mode.

It’s also worth remembering that pacing isn’t a yes/no concept. You’ll naturally pace some things better than others, you can pace a little and still see benefits. All pacing is good pacing, but there’s usually room for improvement.

What are some good ways to help people ‘stick with’ pacing in the long-term?

If you get it right, the results sell themselves. Pacing doesn’t always mean you *can’t* over-do-it. It’s about being aware of the consequences and planning for those. It’s *informed* decision making.

Make pacing your version of normal.

I really hope that this gives you an insight into pacing and was helpful for you! A huge thanks to Jo for giving me so much to think about! You can find her website at jboccupationaltherapy.co.uk, to learn more about her Pacing Masterclass and other services. You can also find her on Twitter and Instagram.

If you enjoy my content, the biggest way you can support me is by subscribing to my newsletter.

8 thoughts on “Q&A: Pacing & Chronic lllness”

Thank you for this series, Natasha and Jo! The last post started to change my mind about pacing- there are some things I can’t break up (showers!) and other things I don’t want to break up (writing!) but I think if I give myself time to think about the long-term gains of pacing (being able to write a little every day instead of a lot once every two weeks!) it’ll come into focus more.

I really needed to read that it’s okay if I pace some things better than others, and that Jo doesn’t pace “perfectly.”

Right now, the concepts you’ve presented are still kind of fuzzy to me- but I think given a little time they’ll change my idea of pacing from “do almost nothing” to “do different things in small chunks.”

Thanks so much, Kat! I’m glad the posts have been helpful.

I definitely can relate to how you’re feeling. A lot of it for me right now is a mindset shift – so rethinking how I choose to use my energy – going from nothing or everything to little and often. There are a few tools and things that I’m slowly starting to implement that I have found have helped, but I’m struggling to keep at it consistently throughout the day. But as Jo told me, one thing paced is more than I was doing before – and that’s a win!

Pacing is always a good idea because work can be stressful and daunting. If you pace, you feel better and more relaxed and it helps you think better and clearly what you want to do next.

Thanks for sharing. Pacing for me has been “0h you’ve done a task and you don’t hurt so much and you still have energy – so I’ll do some more!” Sadly I then feel burnt out suddenly and want to crumble in a heap somewhere! I like the info about taking a break and do something less taxing in between! I always thought feeling exhausted was ok because I tried my best! But I can see I need to be kinder to myself and not to get to burn out point. Xx

Great advice, clearly explained. Thank you.

Thank you!

Thanks so much for really helpful article. I keep it open on my phone and often refer back to it as well as passing it on to others. I thinks it’s the first time I’ve thought of a possible pacing strategy as changing activities rather than stopping to pause an activity. Jo presents some really interesting advice and it feels much more do-able now.

Thanks so much, Beth! I’m glad it was helpful. I’d never thought of it that way before either!